EVANS, the medical missionary, and I were dynamite fishing in the lagoon. It was

capital sport and dangerous enough to supply a thrill for the tyro.

Evans was the only white man in the settlement. His neat bungalow stood alone in

the. centre of the compound, a hundred yards from the jungle. For ten years he had

lived there, solitary, isolated but the devastating effects of the Tropics seemed

to have made few inroads upon him. I had found him interesting company during several

days I was marooned in his village, awaiting the arrival of my schooner I watched

him as he put a bit of fuse on the end of a stick of dynamite, then lighted it and

threw it into the air. It exploded close to the water and soon dead fish began to

appear, belly up, on the surface.

"You have to do this thing right," be observed laconically "Sometimes

my houseboys cut the fuse too short. then things happen! Or if it's too long the

water will touch it before it has had time to explode the cap. Some chaps 'sky' the

stuff so they can have a longer fuse, but it's apt to come down in your lap if you

try that. And I if that happens, well -- the sharks are handy hereabouts to clean

up the debris!"

In between explosions we talked about existing conditions in the islands. I expressed

the opinion that the New Hebridean cannibal was not as black as be was painted; that

possibly he murdered an enemy or two occasionally (which was a shock to no good New

Yorker), but that in the whole he wasn't such a bad fellow. And as for cannibalism,

the actual eating of human beings, that was sheer delusion.

"Cannibalism!" exclaimed Evans. "Say, you people from back home

think that cannibals exist only in the imaginations of novelists and that head hunting,

if it ever existed, at all, is a thing of the past. Why let me tell you, there is

as much unrest and savagery among, the hill natives today as there was when they

were first discovered. For months the hill tribes have been at bloody war with one

another. Hardly a day passes that some poor black wretch doesn't drag his bones down

to my bungalow for treatment; usually he has managed to escape his enemies after

frightful torture, and he arrives riddled with unbelievable wounds."

"But is there nothing that can be done to stop it?" I questioned.

"Oh, a cruiser puts in here occasionally, and if any white men have been murdered

within the last six months fires a few shells into the hill villages. The New Hebridean

islander is treacherous and vindictive, devoid of gratitude, and almost without natural

affection. He will avenge the smallest slight by bloody murder if he can do so from

ambush."

"But what can you do?" I demanded. "You are the only white man in

this settlement. There are only a handful like you on the entire island against hundreds

of unscrupulous black devils. To be sure, they haven't much in the way of arms or

ammunition, but from all I have heard their poisoned arrows and blow guns are not

playthings."

"Well," replied Evans, "I seem to have about as much influence over

them as any one. I'm not a trader, you see. I'm not trying to get anything out of

them. I tie up their cuts and dose 'em with quinine and talk to 'em about Jesus.

I've had it in mind for some time to go to Malekua, the largest of the hill villages,

where most of the fighting has been done, and see what I can do to make them lay

down arms. You never know where this constant scrapping may end. How would you like

to come along?"

It was a rare opportunity, and I assented with alacrity.

"It won't be all beer and skittles," observed the practical medical missionary.

Life up in the mountains is primitive, to put it mildly. And it's not without danger.

We will have to go unarmed, for the natives are suspicious of every one, and if we

went with weapons they would probably kill us from ambush like a couple of snipe.

Are you game?"

And so it came about that two days later we started on our expedition into the interior,

not without a few misgivings on my part. I had not been in The New Hebrides very

long, and the tales I had heard of the inhabitants had not been of a sort to increase

my confidence in them. But the forbidden and the dangerous has a peculiar lure for

most of us. Who would prefer to sit peaceably on a broad veranda, sipping cool drinks,

when he might witness the weird rites and age-old ceremonies that have clung to the

savage inhabitant of the New Hebrides from time immemorial?

WE went unarmed, Evans and I up into the hill country without guide or carrier, for

Evans knew the trails of the jungle as well as I knew the streets of my home town.

We left the

settlement in early morning, expecting to reach the cannibal village at noon..

The first part of our voyage was accomplished by canoe, up a sluggish green river

that wound its tortuous way into the heart of the jungle. Lush green trees and tangled

vines formed an impenetrable wall on either side of the river. Insects hummed an

unceasing accompaniment to the dip of our paddles; crocodiles lay motionless as logs

upon the surface of the stream, waiting until we were almost upon them before slipping

noiselessly beneath the water. All morning we paddled on against the sluggish current.

Not a sound of animal or human broke the death-like stillness. There was something

sinister, something that made the flesh creep, in that awful silence. The trees might

have been filled with a thousand watching eyes, for all we knew. Anything might have

happened in that spot.

It was with relief that we landed at the foot of a high mudbank. We pulled the canoe

up out of reach of the current and started out along the jungle trail. It was little

more than a wild pig path, but Evans read the signs of the big trees with the unerring

instinct of a native, his eyes constantly on the alert for the poisoned arrows and

traps with which bill cannibals fortified the approach to their citadel.

Soon a new sound came to my ears. It mingled with the low drone of the insects and

became part of it, but it bad a rhythm, a punctuated beat.

"We have been seen," observed Evans. "Do you bear the drums?, They

are signaling Malekua. Those drums carry for miles. If we had brought one of the

houseboys we might have known what they are saying. Nothing complimentary, I'll wager.

We'll be in the village shortly. This heat is wellnigh unbearable."

Half an hour later, exhausted after the long climb in a climate that doesn't invite

exercise, we found ourselves upon a well defined trail. Evans opened his mouth and

called out in a loud voice. Instantly I was aware of sounds on all sides of us. The

forest, hitherto so silent, broke into life. In amazement I looked about me and saw

that the trees were filled with savages. They seemed to be older men for the most

part, elaborately and fearsomely arrayed. They must have been shadowing us for miles,

stalking us with the skill of tigers, for not one indication of their presence had

come to my knowledge. Evans said afterward that he had been aware of our ominous

escort for some time, but had forborne to alarm me. I recognized instantly the wisdom

of having come unarmed. Equipped with rifles or revolvers we would have been powerless

against such a horde, and our very defenselessness disarmed suspicion.

Completely surrounded by our wild looking escort, we entered the cannibal village.

I had an impression of a row of grass houses grouped about a square, each one shaped

like a beehive. Idol posts, grotesque and obscene, stood by every doorway. One house,

high-peaked and thatched of roof, towered above the others. It was the hamil, the

priest house. Evans led the way to it.

We stooped to enter the low doorway, and for a moment my eyes could make out nothing

in the deep gloom. Then I saw a row of old men sitting on the mats naked except for

the most fragmentary of loin cloths. The tails of pigs were stuck through their ears,

their bodies decorated with a repulsive tattooing of raised scars, their faces were

savage, simian. Their evil, suspicious little eyes, looking out at us from under

low and slanting foreheads, held an unwavering glitter eyes as expressionless and

fixed of purpose as those if a snake. I wondered how Evans could have believed that

he held the confidence of these creatures.

The medical missionary was addressing them in his best Malekuan. He told them --

he afterward informed me -- that rumors of warfare had been coming to his ears, that

he was among them to care for their wounds, bringing me as his assistant; they knew

that he had always been their friend; be had tended their ills without asking return;

surely they could trust him this time. He went on to say that so much fighting was

bad for their village, that their taro patches were being destroyed, cocoanuts cut

down, plantations laid waste. They would better call a, truce. Perhaps with the help

of the various chiefs he, Evans, could bring this about.

The old men were silent for a moment, as if weighing the doctor's statements. Then

they burst into a babel of sound. They informed him that there never could be peace

between the hill tribes; that the Apians, their nearest neighbors, had that week

killed and eaten the Malekuan chief and carried off three women. It was war to the

death. No one should be spared. The young warriors were at that, moment on their

way to the Apian village. Every house should be burned to the ground, every man beheaded

and dismembered, every woman captured and every baby boy put to death! At any moment

we might hear the drums, stationed high up in the mountains, signaling victory --

or defeat. Eat or be eaten, that is the slogan of the New Hebrides. Bloody wars are

fought to the death and no combatant cries for quarter.

THERE was nothing to do but wait far the return of the warriors. We were in an

extremely precarious position. If the Malekuans won they would return to their village

with the head of their enemies, drunk with victory and in the general enthusiasm

that would inevitably follow I doubted the power of Evans's control over them. On

the other hand, if they were defeated this village might be invaded and razed by

the very tribe they had gone forth to conquer, and we would stand small chance of

being spared.

But it was dark by this time, and to have run now would have been a confession of

weakness and would have been more disastrous in all probability than standing our

ground.

Fires were being lighted in the square. An air of bushed expectancy pervaded the

whole village. Every man, woman and child was waiting for the drums to signal victory.

A fire of cocoanut husks had been lighted In one corner of the huge room where we

sat and I began to take account of our surroundings. I saw rows and rows of shelves

upon the walls, where skulls were arranged like so many jam pots, while in an opposite

corner a line of mummies was placed like a barricade, like a screen masking some

holy of holies, some shrine too sacred for the eyes of any but the priest-doctors

to see. They were strange things, those mummies, rare booty for a museum. They looked

like the stuffed skins of men fastened on poles that ran up through the legs and

out at the shoulders. The hands dangled like empty gloves. Bushy mops of hair still

clung to the heads, and the faces had been cleverly -represented by masks of clay

into which huge eyes of mother-of-pearl had been, fitted. Those eyes, fixed and staring,

shone through the gloom with uncanny and startling effect. The bands swayed idly

in the currents of air, and the grisly trophies seemed more than half alive.

One of the old men was busy poisoning the tips of arrows, the poison being a vegetable

juice that had been steeped for weeks in a decaying' corpse I noted the extreme care

with which he dipped a brush of cocoanut fibre into a shell of poison, taking great

pains not to let one drop touch the mats or his bare skin. Whether this had a religious

significance or was merely a sanitary precaution against the power of the poison,

I was unable to tell.

No one spoke. A bush of expectancy and nervous tension communicated itself to all

of us When would the hill-drums signal, and what would their message be?

SUDDENLY the old men sat upright with one accord. Their keen ears had caught something

that mine could not. But the. next moment I heard it, fax off faint, intermittent:

the awaited signal!

Stifling an exclamation, Evans caught my arm. The beats grew louder, the rhythm more

pronounced. I would have given anything to have been able to read it. Instead we

watched its effects upon the faces of the listeners. Their eyes widened, their breath

came quicker, then consternation and sheer terror distorted every countenance. Their

warriors had been defeated!

In a second pandemonium broke loose. The old men sprang to their feet. The cries

of the women and children, who had been in hiding, filled the air. We must flee for

our lives before the victorious Apians descended upon us. The men were gathering

up the skulls in huge baskets. They would as soon have left their own bodies in the

path of the invaders as to have left the skulls of their fathers, for not a cannibal

in the entire New Hebrides but knows what spells of sorcery can be wrought upon him

if one of his possession falls into an enemy's hands.

But a, new sound came to our cars, rising above the cries of the women and the general

uproar of panicstricken flight. It sounded like the ravening cries of a hunting wolf

pack, but I knew that the sounds came from human throats.

"Good God! It's the Apians!" burst through Evans's lips. "We're goners!"

The Apian warriors were already running down the path leading to the village. We

could hear the thud of their bare feet on the bard clay. The air was hideous with

their cries of victory and murder and hate. They were not men, but animals mad with

the lust to kill. The women set up a mighty wailing. Terrified children screamed

anew. The old men, seeing that flight was impossible, bravely sprang enough seized

their spears and sprang to the doorway ready to do battle to the death in protecting

their sacred hamil.

"Come! This way! It's our only chance!" whispered Evans in my ear, and

he pulled me across the room to the corner where the grisly barricade of mummies

guarded their holy of holies. We shoved one of the figures aside and crept into the

dark corner.

The invaders, drunk with victory and the madness of battle, might overlook our hiding

place and we would be safe, at least for a few hours

Peeping out between the chinks in the barricade we witnessed snatches of the massacre

that followed. I saw one old armed with a club of ironwood, lay open the skulls of

two Apians before he fell with a poisoned arrow in his heart. Huge bonfires in the

square cast a blood glow over the whole scene and made the ensuing hours unbelievably

horrible.

THE night seemed alive with madmen; the. air was filled with their deafening cries.

Screams of the stricken rose above the tumult. Evans and I crouched low behind the

barrier of mummies, wondering at what moment we would be discovered. But the invaders

had evidently decided to postpone the sacking of the hamil. There was sterner business

at hand. The bonfires leaped and crackled under new loads of fuel. Voices, shrill

and raucous, took up the rhythm A score of stark naked figures formed a frenzied

circle around the fire. Some instinct older than the memory of man told me what was

to happen; those drums spoke a language I understood. Perhaps it was that untold

aeons ago, savage fur-clad ancestors of my own race shuffled a similar tread about

a bonfire, with similar intention!

"They have gone absolutely mad!" whispered Evans. "I have never seen

them like this. That is the feasting song they are chanting. We have got to escape.

They are beginning to drink kava and soon will be drunk, but we might be discovered

at any moment. It would be the end."

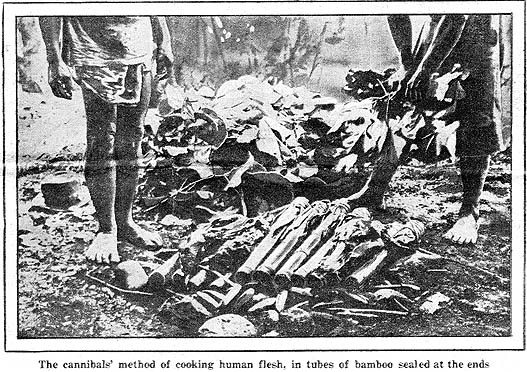

Through holes in the bamboo walls we could see the fires leaping skyward in a shower

of sparks. The captured women and children had all been herded in the farther end

of the square. Then, in horror, we saw The Apian warriors behead the bodies of the

slain men and hold aloft their dripping trophies as they danced like fiends incarnate

about the fire. The heads were then wrapped in leaves and laid in the embers; arms

were cut off at the elbows and treated in similar fashion. I turned away, sick with

repulsion, overcome by a strange weakness. . . .

The savages continued their mad orgy until they fell exhausted to the ground. The

heads and limbs of the slain Malekuans smoked in their leafy wrappings. A horrible

odor of burning flesh, never to be forgotten, filled the air. The hour of the feast

was at hand.

"We. must make a break for it! It's our last chance!" cried Evans in a

hoarse undertone.

Crawling on our bellies we crept across the floor from our hiding place to the doorway.

Only a faint swish came from the mats as our bodies scraped across them, inaudible

to the revelers, but the pounding of my heart sounded in my ears like the crack of

doom. The moon bad risen and added its pale glow to the light of the flames.

"Now!" breathed Evans, rising swiftly to his feet.

Like two fleet ghosts we sped across the square to the open path. Once on the trail

we might outrun our drunken pursuers; and if our canoe was where we had beached it

we could leave them far behind. But we had underrated our enemies.

As we tore down the moonlit trail, we heard a cry of astonishment rise behind us.

Then angry shouts came to our ears and we knew that the chase was on. Fear lent wings

to our heels and we tore down the trail to the river at a pace that I have never

achieved on foot before cry since. The cries of the maddened wolf pack at our heels

told us that one misstep, one twisted ankle or stumble in the darkness meant torture

and death.

Suddenly we were upon a high bank. The river lay almost beneath our feet. We slid

and fell through the mud. The canoe was where we had left it. In a second we were

well out in midstream, paddles plying madly in the water. The cannibals. having no

canoes, followed us along the river bank through the jungle. The density of the foliage

and the swampy nature (if the land on both sides of the river prevented them from

coming close to us and protected us from their poisoned arrows. We would have made

a shining target in. the moonlight.

We could hear them crashing and tearing their way through the trees, sobered Considerably,

it seemed, by their anger. The current and our frenzied paddling sent us along at

a swift pace, but as we approached the sea we began to wonder if we would regain

the beach and the settlement before our pursuers, for they seemed to have found some

trail that made their progress more swift.

WE beached the canoe within a hundred yards of the mouth of the stream

and tore across the intervening space to the shelter of the compound. Already the

cannibals were at our heels. We could hear their triumphant shouts as they emerged

from the trees, hot upon our trail. The terrified houseboys of the compound had armed

themselves with rifles and any weapons that lay at hand.

WE beached the canoe within a hundred yards of the mouth of the stream

and tore across the intervening space to the shelter of the compound. Already the

cannibals were at our heels. We could hear their triumphant shouts as they emerged

from the trees, hot upon our trail. The terrified houseboys of the compound had armed

themselves with rifles and any weapons that lay at hand.

We dashed across the beach to the shelter of Evans's house and reached it not one

minute too soon. At the same moment the houseboys fired a volley into the ranks of

the approaching savages. They halted in consternation, and we could see them duck

for shelter. They evidently held a conference, then decided to attack, for in another

moment we saw them advancing in formidable array, spears bristling and blowguns in

position. Four rifles spat fire and four painted blacks sprawled in the sand, but

the band advanced.

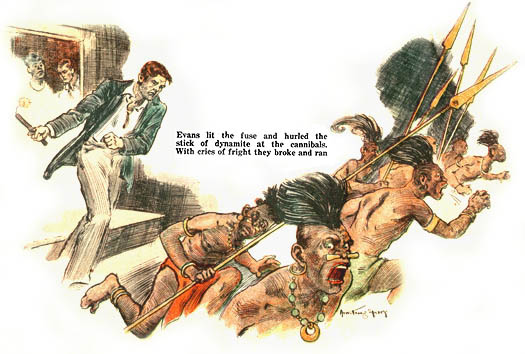

Then Evans did a brave thing.

I saw him reach into a box, take out a black stick of something, seize a match. In

another moment he had opened the door and was on the veranda. A shout went up from

the savages. For a second they were so surprised that they paused; the New Hebridean

is unused to bravery. It was that split-second pause of theirs that saved us.

Evans had struck a match. I saw that what he. held was dynamite. The fuse caught,

and he hurled it at the cannibals.

There is nothing a native fears so much as dynamite. To him it is bound up with sorcery

and witchcraft. With cries of fright, strangely at variance with their former victorious

confidence, they broke and ran.

The dynamite exploded and shook the little house like an earthquake. From the

trees came the crash of timber and the terrified cries of the retreating savages.

Nothing on earth could have tempted them back within range of the dynamite.

The houseboys were shivering with fright. I saw that an arrow, barbed with a poison

as deadly as that of a rattlesnake, had torn clean through the sleeve of Evans's

shirt, leaving the skin, by some miracle, untouched. He pulled the arrow from the

cloth, mopped his forehead and sat down.

"Well, that was a narrow squeak," he observed dryly. "We're safe anyway,

safe until next time!"

© The Estate of Armstrong Sperry