Note from the Webweaver: This is an early example of the author's fiction, based on his experiences as a member of the crew of Hawai'i's Bishop Museum's actual ethnological expedition through the South Pacific aboard the Kaimiloa in 1924-25.

It was November, 1924, that the Bishop Museum of Honolulu invited me to join an expedition

to the South Seas. Medford Kellum of Florida had bought a four-masted schooner, fitted

it up as a yacht, and had planned a trip to the far-flung archipelago. I went technically

as "assistant ethnologist," but in reality as the artist of the expedition.

It was a rare opportunity to visit islands almost unknown, that had scarcely been

touched by civilization; places unseen by the eyes of white men for generations since

their discovery by those adventurous old-time mariners who sailed the seven seas.

Ka-imi-loa was the name of the newly-christened yacht, and the translation of

the Hawaiian syllables means "The Long Search." She sailed from Hawaii,

manned by a crew of sixteen Marshall Islanders. In addition to Mr. Kellum and his

family, there were six scientists from the Bishop Museum. Many months later, the

yacht sailed back again to Hawaii, laden with South Sea loot: carved tortoise-shell

ornaments, sharkskin-covered war drums, porpoise-tooth necklaces and headdresses

of old men's beards; there were devil-fish hides used for scraping the perfume from

sandalwood, mats and fans of infinite variety, and pearls of every size, shape and

hue.

After a cruise of some weeks, during which we touched at many ports, we arrived at

Tahiti, where the Ka-imi-loa left us at work and sailed back to Hawaii for provisions

and repairs. Some months of mellow and beautiful weather found me wandering here

and there in the islands.

Many were the days I spent in the sea and upon it, swimming, fishing, idling on the golden sands. The natives, young and old of both sexes, are remarkable for their prowess in the water. The Australian crawl is unknown to them and they have little speed, but when it comes to endurance, they could put most of our Olympic stars to rout. Cases of natives who have lived several days in the water, swimming all the time, are too well known to be cited.

It was about this time, while I was fishing one day in a small canoe beyond the outer reef, where the swells of the Pacific lifted and dropped the craft in gentle monotony, that I had the most thrilling experience of my life, and one that I should never care to repeat.

My good friend Terii was paddling. Terii it was who had moved bodily out of his house, taking his family with him, that I might have a comfortable place to live in during my stay on the island. And it was Terii who saw to it that there was always steaming breadfruit and banana poi at meal times. And Terii's wife who washed my scanty wardrobe in the river and pounded it on the rocks until it was in an alarmingly frail condition. And who was it but Terii who scouted the island for old men and women who could teach me the folklore of their race? If I wanted a model, Terii was there to find one; or a cocoanut, a fish, a canoe, not matter. There is no hospitality in the world more whole-souled, more unselfish than that of the Polynesian.

I had often gone fishing with Terii, and together we had caught tuna and bonita, sharks, octopus, and ulua. We had tracked down in the sand of the lagoon the weird and palatable varo, and the deadly nohu. We had speared eels in the rivers and shrimp in the ponds. To-day we were after the giant ahiahi that were running in silver hoards along the outer reef. Several other canoes were fishing nearby.

My hook was carved from mother-of-pearl with a few hog bristles attached to the end; the barb was the sharpened tooth of a hog ingeniously attached to the proper place.

Terii kept the canoe plying back and forth, and over my shoulder I could catch the occasional glitter of my pearl hook in the water. The giant fish were playing in schools around us and seemed a bit wary of the shining bait. But suddenly the canoe gave a lurch as my line tautened.

"Ahiahi!" cried Terii, excitedly. "Pull! Pull!"

The surface of the water a few fathoms away boiled as if being stirred from below by a great silver spoon. It required considerable skill and speed and strength on Terii's part to anticipate the rushes of the fish. One false move and we might easily be swamped before I could loosen the end of the line. The ahiahi would make a desperate dash toward the opening in the reef, hoping, perhaps, in some obscure corner to escape his foe. Occasionally he would pause as if in perplexity, then leap clear out of the water, twisting in the air like a great silver harlequin, only to fall back on the water with a resounding splash. The struggle lasted a good hour. Natives in the canoes nearby called out encouragement and advice. Terii's eyes shone with the delight of conquest.

But now the water began to calm a bit. The great fish was tiring. He had made a good fight, and I could see him through the clear water, as through plate glass, moving in slow circles. I began to pull steadily in.

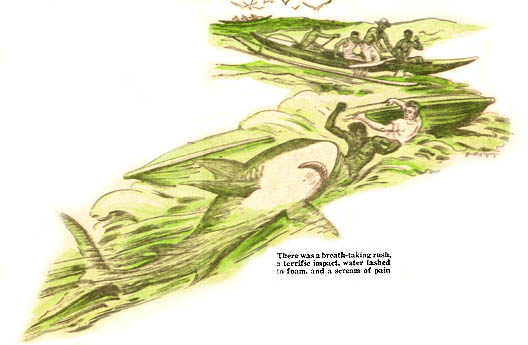

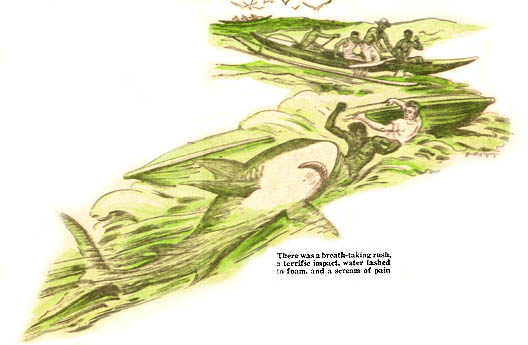

My catch was so close to the canoe that we could see the entire silver body of him, when with the suddenness of a clap of thunder, a monstrous gray shape rose beneath our canoe and the ahiahi disappeared as if engulfed by a dark cloud.

I pulled aboard only the gaping head. The body had been severed cleanly by the teeth of a shark. The great monster rolled slightly on his back as he passed, and we could see the white of his belly and the yawning chasm of his mouth, that looked as if it were curving into a sardonic smile.

With a cry of rage, Terii made a lunge at the shark with his paddle, striking him a resounding blow on his side.

Then things began to happen!

One flip of the mighty tail and out canoe rose beneath us, up-ended, and we were thrown into the sea. I had catapulted some twenty feet through the air, and came up to find that Terii was quite a distance away, looking anxiously for me. He gave me a great cry when he saw me and pointed over my shoulder. I looked -- and saw the polished steel-blue fin of our enemy the shark moving in slow circles not twenty-five yards away.

Blind fear took possession of me. A man on land, in his own element, can slay a lion or put an elephant to rout, but in the water he is at the mercy of any deep-sea monster. Terii started swimming toward me, crying out "Tamai! Make a splash! Splash!"

It galvanized me into action. I flailed the water with my arms. Would the other canoes ever reach me? The circles cut by the steel-blue fin were narrowing ever so slightly. In the clear water I could see perfectly the long dark shape.

It was a tiger shark, feared by everything that swims in the sea, the only one I had ever seen. The blood congealed in my veins.

Our friends in the other canoe were paddling madly to our assistance, shouting encouragement. Terii had reached my side, and threw himself before me, commencing a mighty splashing and calling down the wrath of the sea gods upon the head of our enemy.

Our rescuers had almost reached us, and the shark, sensing that he was about to lose him prey, paused in his circling for one split second. I knew instinctively what was to happen.

There was a breath-taking rush, a terrific impact, water lashed to foam, and a scream of pain. The strong arms pulled me out of the water into the canoe...

Not until we neared the shore half an hour later did I realize what had happened: the old men who were paddling the canoe chanted a dirge of disaster. Terii, my friend Terii, who had put himself between me and death, lay at my feet in a pool of blood on the floor of the canoe. I saw the both his hands were gone at the wrists.

Many times since that day, the words of the old parable have come back with new and startling significance:

"Greater love hath no man than this: that he lay down his life for a friend."

© The Estate of Armstrong Sperry